Understanding Postpartum Depression: A guide for Parents of Premature Babies

In the first two weeks following childbirth, many mothers experience what is known as postpartum “baby blues”. This is characterized by mood swings encompassing feelings of anxiety, sadness, and irritability, along with disruptions to sleep patterns (either insomnia or excessive sleeping). These symptoms are triggered by the sudden decline in estrogen and progesterone hormone levels that occur after the baby is born1.

However, one in seven new mothers the postpartum “baby blues” evolves into something more enduring known as postpartum depression (PPD)1. Postpartum depression encompasses a spectrum of symptoms including depression, anxiety, feelings of shame or guilt, withdrawal from loved ones, and difficulty of finding pleasure in once-beloved activities. The bonding process between a mother and newborn can also be strained under the effects of PPD2.

New parents are often overwhelmed when adjusting to life with a newborn, however, the stress of having a premature baby and the challenges of the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) environment can compound these feelings of anxiety and depression in parents. Parents of premature babies may face unique stressors such as uncertainty about their baby’s health, prolonged hospital stays, lack of bonding with the baby, and the potential various medical interventions that preemies often need3.

It is crucial for parents of premature babies to recognize when postpartum depression may be at play. If you have been experiencing any of the following symptoms for more than 2 weeks, please reach out to your healthcare provider:

Research indicates that mothers of premature babies or infants with prolonged hospitalization face an increased risk of experiencing postpartum depression4. In addition to this, various risk factors for postpartum depression include:

Studies have underscored the significance of hospital culture in addressing the psychological needs of mothers of a preterm infant. The admission of premature babies into the NICU has a significant impact on the entire family. Involvement from day one of neonatal nurses and clinicians is crucial for optimizing the care for mothers immediately after preterm birth and during the infant’s hospitalization, in order to help mitigate postpartum depression. In the NICU environment, new parents often find themselves unable to engage in anticipated parenting activities such as holding, bathing, feeding, and comforting their infant6. This can lead to feelings of loss of a parental role, helplessness, and inability to protect their baby as clinical team members assume primary caregiving responsibilities instead7. Hospitals can address these emotions by adopting a family-integrated model, allowing parents to actively engage in all aspects of their infant’s care during their NICU stay6. Utilizing tools such as webcams or virtual platforms to provide visual updates on their child has been shown to promote attachment and bonding. Significant milestones, such as “moving to an open crib” or “bottle feeding”, can be shared with caregivers through GDPR/HIPAA-compliant platforms. Involving parents in their preemie’s NICU journey can support maternal- and paternal-infant bonding and reduce the risk of postpartum depression6.

There are a few additional protective factors against postpartum depression, including:

- Breastfeeding, due to its facilitation of maternal-infant bonding

- Social support, covering emotional, financial, and practical assistance

- Regular engagement in physical activity8

In summary, postpartum depression can significantly impact parents of premature babies, adding to the challenges already inherent in adjusting to life with a newborn. By recognizing the signs of PPD and implementing strategies to support parental well-being both at the NICU and in the home setting, healthcare providers can help alleviate the burden of postpartum depression for parents of premature babies and facilitate a smoother transition into parenthood.

REFERENCES

1 Mughal, S., Azhar, Y., & Siddiqui, W. (2022). Postpartum Depression. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

2 Faisal-Cury, A., Bertazzi Levy, R., Kontos, A., Tabb, K., & Matijasevich, A. (2020). Postpartum bonding at the beginning of the second year of child’s life: the role of postpartum depression and early bonding impairment. Journal of psychosomatic obstetrics and gynaecology, 41(3), 224–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/0167482X.2019.1653846

3 Hendy, A., El-Sayed, S., Bakry, S., Mohammed, S. M., Mohamed, H., Abdelkawy, A., Hassani, R., Abouelela, M. A., & Sayed, S. (2024). The Stress Levels of Premature Infants’ Parents and Related Factors in NICU. SAGE open nursing, 10, 23779608241231172. https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608241231172

4 Tahirkheli, N. N., Cherry, A. S., Tackett, A. P., McCaffree, M. A., & Gillaspy, S. R. (2014). Postpartum depression on the neonatal intensive care unit: current perspectives. International journal of women’s health, 6, 975–987. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S54666

5 Ghaedrahmati, M., Kazemi, A., Kheirabadi, G., Ebrahimi, A., & Bahrami, M. (2017). Postpartum depression risk factors: A narrative review. Journal of education and health promotion, 6, 60. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_9_16

6 Nyberg, N. (2023). Importance of connectedness to attachment for NICU parents. Neonatal Intensive Care, 36(1).

7 Woodward, L. J., Bora, S., Clark, C. A., Montgomery-Hönger, A., Pritchard, V. E., Spencer, C., & Austin, N. C. (2014). Very preterm birth: maternal experiences of the neonatal intensive care environment. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association, 34(7), 555–561. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2014.43

8 Vigod, S. N., Villegas, L., Dennis, C. L., & Ross, L. E. (2010). Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression among women with preterm and low-birth-weight infants: a systematic review. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology, 117(5), 540–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02493.x

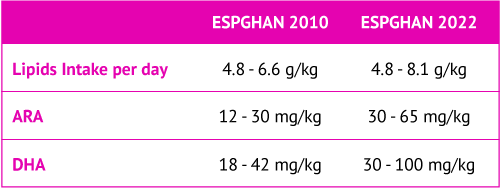

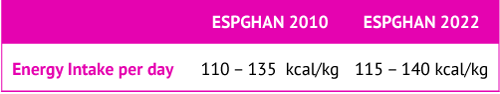

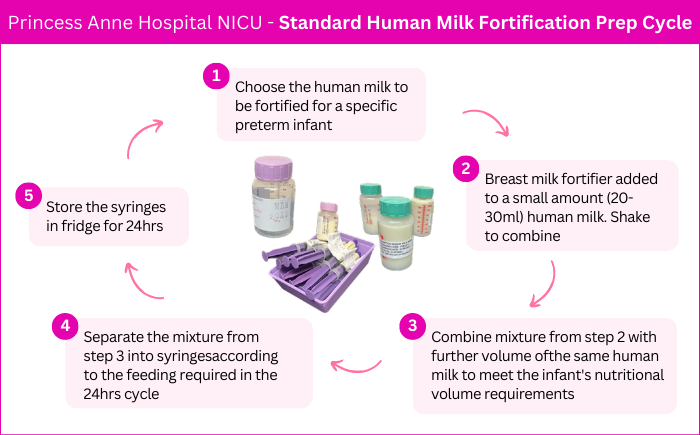

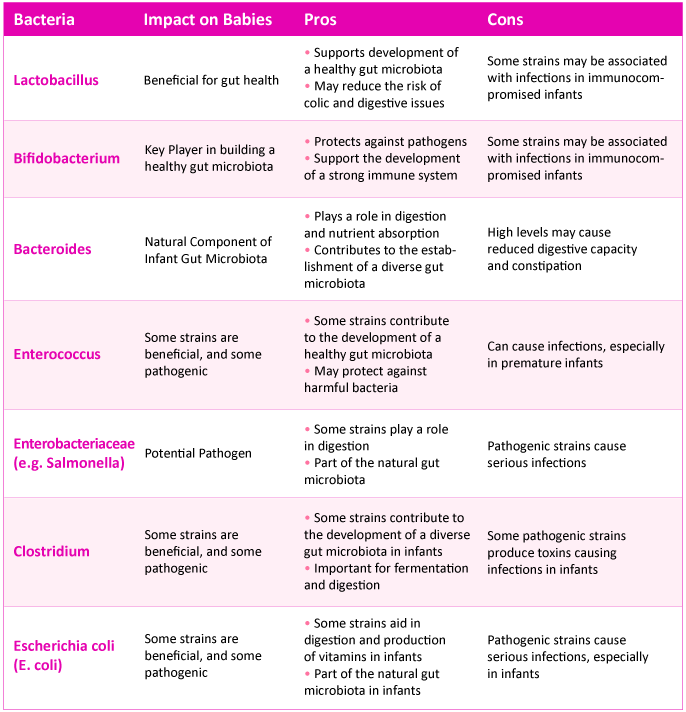

The European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) is a group dedicated to promoting the health of children with a focus on the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and nutritional needs. ESPGHAN disseminates science-based information and advice on the best practices to meet the nutritional needs of children. ESPGHAN has four special interest groups dedicated to specific aspects of pediatric health: gut microbiota and modification, clinical malnutrition, neonatal nutrition, and childhood obesity. The neonatal nutrition committee of ESPGHAN provides neonatal professionals with quick and easy access to recommendations on nutrient intakes and nutritional practice in preterm infants with birth weight less than 1800 g.

The European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) is a group dedicated to promoting the health of children with a focus on the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and nutritional needs. ESPGHAN disseminates science-based information and advice on the best practices to meet the nutritional needs of children. ESPGHAN has four special interest groups dedicated to specific aspects of pediatric health: gut microbiota and modification, clinical malnutrition, neonatal nutrition, and childhood obesity. The neonatal nutrition committee of ESPGHAN provides neonatal professionals with quick and easy access to recommendations on nutrient intakes and nutritional practice in preterm infants with birth weight less than 1800 g.